Pilsen Beer

01/18/2021

The Family of Pilsners

By Jack Horzempa

A topic that I have often read on Internet beer discussion forums is: what type of Pilsner is Brand X from Brewery Y and what is really the difference between the different types of Pilsners?

This article will address this topic along with a discussion of the history between the differing types of Pilsner beers and the ingredients & brewing processes involved in producing these differing types.

Types of Pilsners

In Figure 1 there is a depiction of three types of Pilsners (Bohemian Pilsner, Classic American Pilsner and German Pilsner) along with a snapshot of some differing features of these three types.

Figure 1 Pilsner types

History of the different types of Pilsners

Bohemian Pilsner

The first (original) Pilsner was brewed in 1842 by the Bavarian brewer Josef Groll who traveled to the town of Pilsen, in what is now the Czech Republic, to help the locals brew a better beer. The lore is that the citizens of Pilsen were unhappy with the quality of their existing beers and that by bringing in an experienced brewer they could change things. And Josef Groll did indeed change things.

Bavarian lagers were historically dark, but Groll created a new pale lager in Pilsen. He achieved the lighter color by kilning the malt at a lower temperature, a technique he and other Continental brewers borrowed from Great Britain. Today we call this ultra-pale malt Pilsner malt.

Another distinguishing feature of the new beer is that it was brewed using locally grown Saaz hops and very soft water, i.e. very low in dissolved minerals. The resulting beer became a hit, and we know that beer today as Pilsner Urquell (Urquell is German for “original source”). Pilsner Urquell is marketed as “The Original Pilsner.”

Application of the term innovation to beer is popularly debated, but the development of Pilsner Urquell was indeed an innovation, one which would have major repercussions for brewing in the 19th century and beyond.

Classic American Pilsner

It was not just European beer drinkers that wanted to drink golden colored lagers. The challenge for producing a beer like Pilsner Urquell in America was a difference in barley. The predominant type of barley grown in North America was 6-row barley vs. the 2-row barley grown in Europe. The 6-row barley was better suited for growing in the climate of North America. The issue with 6-row barley when it comes to brewing a golden beer is that it is higher in protein as compared to 2-row. Brewing an all malt golden beer in the America would yield a beer that suffers from chill haze – a hazy appearance when the beer is cold. The American beer drinkers of that time preferred to drink their beers cold so this chill haze issue was a real problem. It should be noted that chill haze was not too much of a problem for the others beers being produced in America in the mid-1800s since they were typically darker in color (e.g., amber/dark ales, dark Bavarian Lagers, etc.).

Thankfully there was a brewing scientist who came to the rescue. Anton Schwarz immigrated to America in 1868 from the Austrian Empire. “He was educated at the University of Vienna, where he studied law for two years, and at the Polytechnicum, Prague, where he studied chemistry.” The year after he immigrated to the US he wrote a seminal article entitled “Brewing with Raw Cereals, Especially Rice” in American Brewer magazine (1869). What Anton Schwarz recognized is that by adding some adjuncts (e.g., rice, corn) to the grain bill the overall content of protein was diluted since the adjuncts contained little protein and consequently the resulting beer would not suffer from chill haze. There was also the added benefit that the beer brewed using adjuncts would have improved beer stability. This improved beer stability was a great asset since American beer consumers drank quite a bit of bottled beer. The information that Anton Schwarz provided was quite an innovation for American brewers.

Below is how Anton Schwarz is lauded in the book American Handy-Book of the Brewing, Malting, and Auxiliary Trades by Wahl & Henius, 1902, page 711:

“It was Anton Schwarz who first advised the employment of rice and subsequently of Indian corn, which is so abundant in this country. The stubborn perseverance with which he sought to convert conservative brewers to his ideas and finally succeed in doing and, last, not least, the discovery of suitable methods to scientifically apply them, entitles him to be called the founder of raw cereal brewing in the United States.”

German Pilsners

German breweries recognized a demand for these golden beers and began producing their own imitations in the 1870s. On its website, the Radeberger brewery claims to have produced the first Pilsner in Germany:

“Sometimes it’s the small town heroes who catch the world off guard and surprise us when we least expect it. That’s what happened in 1872 when five local men of distinction from the small town of Radeberg not far from Dresden decided to teach us all a thing or two about beer. Unhappy with the taste of the beers of their time, they set out to create something better.

Their desire laid the foundation of Radeberger Pilsner, the inventor of our famous German Pilsner Culture.”

Brewing a Pilsner

The various types of Pilsner have a number of qualities in common:

-

Pale in color

-

Moderate alcohol content (typically around 5% ABV)

-

Fermented using lager yeast strains at cool temperatures (e.g., 45 – 55 °F)

-

Cold conditioned (lagered) for a month+

-

Notably hoppy in all the three phases: bittering, flavor and aroma

But there are differences in both ingredients and brewing process (some discussed above) which will be further discussed.

Grain selection and wort production

The principle grain in producing a Pilsner is barley malt.

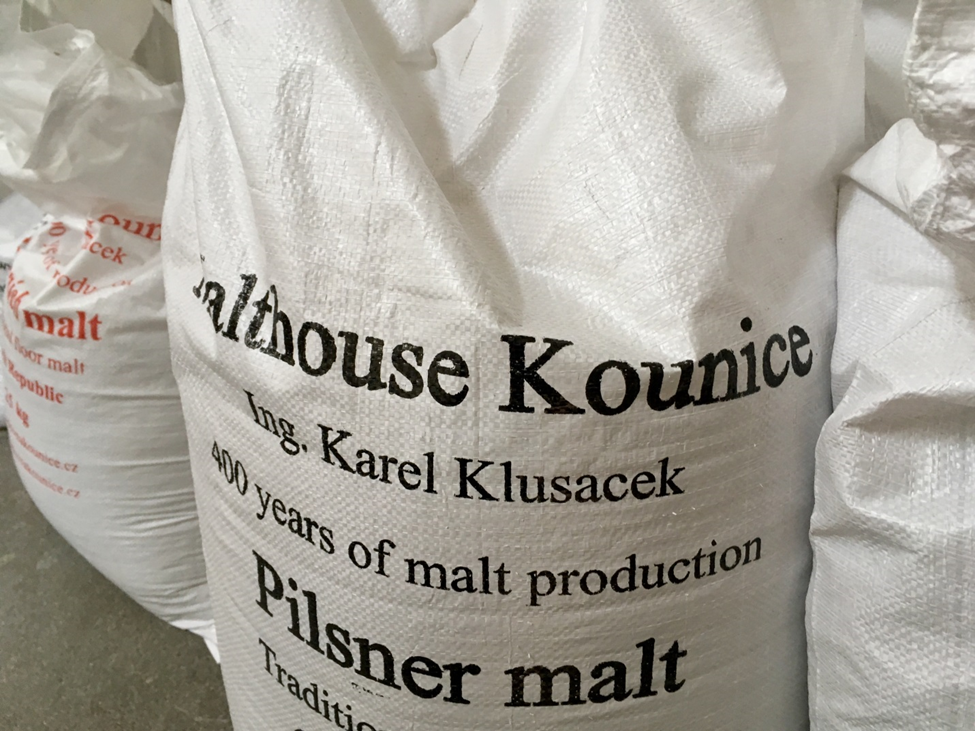

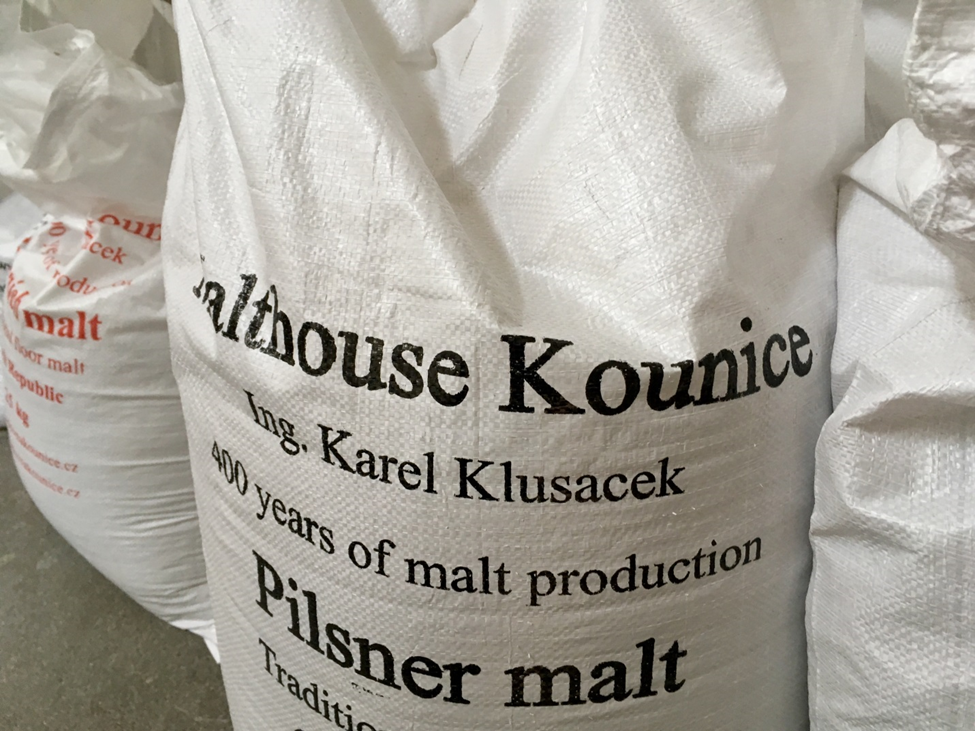

For the case of Bohemian Pilsners (Czech Pale Lagers) the malt is Pilsner Malt which is produced from barley grown in the Czech Republic (typically the region of Moravia). For the case of Pilsner Urquell the barley is purchased by the brewery where they malt the barley at the brewery. Otherwise the Pilsner malt is purchased from a Czech Malting Company.

Malt goes through the process of mashing to convert the starches in the malt to a sugar liquid solution which is called wort. The resulting wort is then fermented by the lager yeast. The method of mashing to create the Bohemian Pilsner of 1842 was decoction mashing whereby a portion of the malt and liquid would be removed from the mashing vessel and boiled and subsequently returned to the mash vessel to increase the heat to a proper temperature to activate enzymes to convert starch to sugars. Pilsner Urquell to this day is mashed this way via a triple decoction mash. The high heat used to boil the malt and liquid during the decoction steps caramelizes some of the sugars and the resulting wort will experience some darkening. In addition, compounds called melanoidins are developed which provide a rich malt character to the resulting beer along with increased fullness to the beer’s body. One of the distinguishing features of Bohemian Pilsner as brewed in the Czech Republic is that decoction mashing is consistently employed.

German Pilsners are also produced using Pilsner Malt which are typically produced by German (or other European) Malting companies. Decoction mashing was employed in the past but due to the higher energy costs of this process most German breweries today instead employ a step mash. The prevalent step mash employed is referred to as the Hochkurz Mash whereby the malt is mashed to achieve two steps in temperature for activating enzymes to convert the starch to sugars and then one more step to denature the enzymes (referred to as a mash out). The net result is that both the combination of differing malts and a differing mashing regime means that the German Pilsner will typically differ from a Bohemian Pilsner in both color and malt flavor character; the German Pilsner will be very light in color (typically straw colored) and there will be a lesser amount of malt flavors from melanoidins (i.e., a less rich malty character).

The Classic American Pilsner is quite different from the other two types since instead of Pilsner Malt a 6-row Pale Malt is used accompanied by a judicious amount of adjunct (either corn or rice) as was previously discussed. This innovative combination result in beers light in color without the issue of chill haze but means that the resulting beer will have a differing malt/grain flavor character. In comparison to a Bohemian Pilsner or German Pilsner the malt/grain flavor is a bit more neutral in character, with those beers brewed using rice being the most neutral while those brewed using corn having a bit of sweetness aspect to it. If raw rice/corn is used there is a need to perform an augmented mash referred to as a cereal mash (or overall: American Double Mash). If flaked corn or flaked rice is used than a single temperature infusion mash can be utilized instead.

Hops

The Bohemian Pilsner is fairly simple as regards hops since only Czech grown Saaz hops are used. The Saaz hops are typically added three times during the boil of the wort with the first addition being for bittering, the second addition for flavoring and the third addition towards the later part of the boil to augment aroma. Hops are generously utilized throughout with Pilsner Urquell having 40 IBUs (International Bittering Units). These beers may not seem to have this level of bitterness since there is a rich maltiness to these beers which can provide some offset to the perceived bitterness and the soft water has an impact as well (to be further discussed).

German Pilsners are often brewed using Noble Hops (i.e., Hallertauer Mittelfruh, Tettnanger, Spalt, Saaz) but German brewers will also use some other German grown hops as well. Some examples of relatively newer hop varieties which could be used are Saphir, Hersbrucker, and Perle. Just like the Bohemian Pilsner a triple hopped schedule is typically used for brewing the German Pilsner: bittering, flavor and aroma. Within Germany there is generally a difference in the level of hoppiness (e.g., bittering) between the Pilsners of Southern Germany and Northern Germany with the Pilsners of Northern Germany often being more hoppy (brewing water plays a role as well as will be further discussed). On average across brands a German Pilsner as brewed in Germany today will have less than 30 IBUs.

Classic American Pilsners as they were brewed in the later 1800’s would typically use domestic (i.e., Cluster) hops for bittering but use ‘better’ imported hops for flavor and aroma additions. The types of hops used for the flavor/aroma additions would be Hallertauer Mittelfruh, Saaz, and Styrian Goldings. As for the other Pilsner types, hops would have been generously utilized for all three aspects: bittering, flavor and aroma. Given the fact that Classic American Pilsners have a more neutral malt flavor profile the result is a beer that permits the hop qualities to really shine. In the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) style guidelines a range of 25 – 40 IBUs is listed.

Brewing water

By amount the largest ingredient used to brew beer is water. This is often the ingredient that is least considered but the qualities of brewing water will have a sensory impact on the resulting beer.

As has been mentioned the brewing water of Pilsen is very soft. The water coming from the wells at the Pilsner Urquell brewery has low mineral content to begin with and during my tour of the brewery the tour guide pointed out the facility where they even further reduce the mineral content. This very low amount of minerals, particularly the low amount of sulfate, will result in the beer having a soft aspect to it which some folks describe as being a fine bitterness (in contrast to a more coarse bitterness).

The brewing water of Germany will vary mostly in a South to North aspect. In Southern Germany the water used to brew the Pilsners tends to be lower in mineral content while the water used to brew the Pilsners in Northern Germany will have increased mineral content; in particular there is a greater amount of sulfate. This difference in brewing water gives the Northern German Pilsner a more pronounced hoppy character accented with a drier finish while those from the South are soft in comparison.

America is a large nation with very varying water conditions. Having stated that, breweries can adjust the water for their brewing needs. For example, Anheuser-Busch operates a dozen breweries across the country but each of those breweries adjusts their water to be the same as used in the original brewery in St. Louis. A water profile recommendation for the Classic American Pilsner would be fairly soft (i.e., not too high in minerals) and low in alkalinity. This water is harder than what would be used at the Pilsner Urquell brewery but softer than the water used to brew a Northern German Pilsner.

My least favorite topic: diacetyl

During the fermentation process all yeast strains (both ale and lager) create a chemical compound called diacetyl. In most cases this diacetyl will be further processed by the yeast into other compounds later in the fermentation process. For most beer styles a perceptible level of diacetyl in the beer is considered a technical brewing flaw. An exception is for Bohemian Pilsner. The BJCP (Beer Judge Certification Program) Style Guidelines states: “Light to moderate diacetyl…are acceptable, but need not be present.” Well the words “light” vs. “moderate” can be quite subjective. There is also the aspect that perceptible diacetyl, which tastes like butter to my palate, may be OK for some folks and undesirable for others (e.g., me). During my recent (2019) two week visit to the Czech Republic (Prague, Pilsen) I drank many draft half-liters of Bohemian Pilsners but the only beer I sometimes had issues with was Pilsner Urquell and principally when at Tankovna Pubs which served Pilsner Urquell directly from tanks within the pub. When I visited the Pilsner Urquell brewery to take a tour I asked the tour guide about this topic. She recognized this situation but since she was not a brewer she had no answer to why there was variability here.

I much preferred the Bohemian Pilsners that had no perceptible levels of diacetyl.

Let’s Drink!

In my opinion there is nothing better than actually drinking beer to best learn about it.

One BIG Caveat: Pilsner is a beer best enjoyed fresh. This can sometimes be a challenge when it comes to imported beers so for this reason tasting US craft brewed versions could be the better option. An old imported beer will be stale and not taste as intended.

Examples of Bohemian Pilsners

Needless to say but the eponymous Bohemian Pilsner is Pilsner Urquell. My preference in the US is the canned version and luckily for me I can often find these relatively fresh.

Another imported Bohemian Pilsner (Czech Pale Lager) is branded as Czechvar for the US market; this beer is branded as Budweiser Budvar in country by the brewery Budějovický Budvar (České Budějovice, Czech Republic).

The qualities of Bohemian Pilsner can vary quite a bit within the Czech Republic. If you ever get a chance to visit I would encourage you to try the following beers: Bernard Světlé Ležák 12°, Kamenice Světlé Ležák 12°, and Únětický Pivo 12°. The terminology of 12° refers to the original gravity of the beer and Světlé Ležák translates to Pale Lager.

Examples of German Pilsners

There is some variability of German Pilsners in Germany with geographic location being a factor. Some examples that I recommend are: Jever Pils (Northern Germany), Rothaus Pils Tannenzäpfle (Southwestern Germany – Baden-Württemberg) and Weihenstephaner Pils (Southern Germany – Bavaria).

There are also a lot of US craft brewed German Pilsners to pick from which likely have variable availability depending on where you live. Some examples are pFriem Family Brewers Pilsner (Oregon), Firestone Walker Brewing Co. Pivo Pils, Austin Beer Garden Brewing Co. Industry Pils (Texas), Summit Brewing Co. Keller Pils (Minnesota), and Sterling Pig Shoats Pilsner (Pennsylvania).

Examples of Classic American Pilsners

There are few examples of commercially brewed CAP beers. They tend to be only available in limited regions and sometimes on a rotating basis: Straub 1872 Pre-Prohibition Lager (Pennsylvania), Fort George 1811 Pre-Prohibition Lager (Oregon), Short’s Pontius Road Pilsner (Michigan), Austin Beer Garden Brewing Co. Rocket 100 (Texas), Upland Champagne Velvet (Indiana), and Fullstream Paycheck Pilsner (North Carolina).

What is mashing?

There is an old saying: Brewers make wort, yeast makes beer.

The way that brewers produce wort is via mashing the grains (e.g., barley malt) whereby the malt is steeped in hot water which hydrates the grain, which in turn activates enzymes which then convert the sugars to starch. There are a number of key enzymes that are needed for the process.

For the production of all malt beers there are various methods for conducting the mash: decoction, step mash and single temperature infusion mash.

For the case of producing Pilsner Urquell a triple decoction process is employed to conduct a mash of varying temperature steps:

-

The mash (malt & water) is first brought to a temperature of 95 °F and then sits for about 20 minutes; this is referred to as an acid rest.

-

A portion of the liquid and some malt is extracted from the mash, brought to saccharification temperature for 20 minutes and then boiled

-

This boiled portion is returned to the mash vessel bringing the temperature in the vessel to127 °F. This is permitted to sit for about 30 – 45 minutes. This is a protein rest which activates proteinase and peptidase enzymes.

-

A second portion of liquid and some malt is extracted and boiled.

-

This boiled portion is returned to the mash vessel bringing the temperature in the vessel to 143 °F. This is permitted to sit for about 30 – 45 minutes. This is the saccharification rest which activates the Beta-amylase enzyme and to a lesser degrees the Alpha-amylase enzyme.

-

A third portion of liquid and some malt is extracted and boiled.

-

This boiled portion is returned to the mash vessel bringing the temperature in the vessel to 163 °F. This is permitted to sit for about 10 – 15 minutes. This final step is referred to as the mash out.

It is easy to see that the above process is time and labor intensive. But perhaps even of greater interest to commercial breweries it is costly from an energy perspective. Pilsner Urquell and other Czech Breweries (some conduct Double Decoctions to save some time and money) still conduct the decoction mash process despite the costs.

The majority of German breweries have gotten away from decoction mashing due to cost considerations. They instead conduct a step mash where they change temperatures via direct heating. The steps for the Hochkurz Mash are:

-

The mash (malt & water) is first brought to a temperature of 144 °F and then sits for about 30 - 45 minutes; this is referred to as the beta amylase rest.

-

The mash vessel is heated to 160 °F and then sits for about 30 - 45 minutes; this is referred to as the alpha amylase rest.

-

The mash vessel is heated to 170 °F and then sits for 10-15 minutes; this is referred to as the mash out.

For brewing a Classic American Pilsner using flaked adjuncts a single temperature infusion mash can be conducted. This method was the preferred mashing method of brewers in Great Britain and was what was conducted by the American brewers in the 1800’s. You place the grains (6-row Pale Malt and flaked adjuncts) in the mash vessel and maintain a chosen temperature between 148 – 162 °F for one hour. Choosing the lower end of the temperature range will result in a more fermentable wort and the resulting beer will have a drier quality while selecting the higher end of the temperature range will result in a less fermentable wort and the beer will have a fuller mouthfeel and perhaps an increased perceived sweetness.

The production of a Classic American Pilsner using raw adjuncts is more complicated since a separate cereal mash needs to be conducted using a separate vessel beyond a mash vessel. This is sometimes referred to as the American double mash and is conceptually similar to the decoction process detailed above.

Bohemian Pilsner vs. Czech Pale Lager

"What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet." - William Shakespeare

For people who don’t live in present day Czech Republic there is a long history of referring to the Pale Lagers brewed there as being Bohemian Pilsners. For example the terminology of Bohemian has a long history with American breweries labeling some of their beer brands using “Bohemian” well over a hundred years ago. One example is Pabst which branded one of their beers as “Bohemian” and this was a bestselling brand for them during the timeframe of the mid-1890’s to sometime in the early 1900’s. The Czechs view Bohemian Pilsner as being an appellation so only the Pilsner Urquell beer would be referred to as Bohemian Pilsner by them. For this type of beer brewed outside of Pilsen the Czech’s would use the term of Světlé Ležák (translates to Pale Lager) and they would provide an additional detail of 12° which delineates the original gravity of the beer using the Balling scale. The Czech breweries also typically produce a Pale Lager of a lower original gravity (and hence lower alcohol content) of 10°. During one brewery tour the tour guide referred to their 10° beer as being “a worker’s beer”.

All contents copyright 2024 by MoreFlavor Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document or the related files may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher.